Weekly Outlook

Is the US really in a recession?

The US just registered two consecutive quarters of “negative growth” – an awkward phrase that means output as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) shrank. (I only wish my waist would exhibit “negative growth”!) Q1 GDP was down 1.6% quarter-on-quarter at a seasonally adjusted annualized rate (SAAR), meaning it was down 0.4% qoq and if that had continued for a year at that pace, it would’ve been down 1.6%. Thursday we learned that Q2 GDP was down 0.9% qoq SAAR, or -0.2% qoq. According to the generally accepted rule-of-thumb, two consecutive quarters of contracting GDP is a recession. That means the US is now in recession, right?

Not exactly. While that’s the informal “rule of thumb” that a lot of commentators use, it’s not how it’s officially determined. The task of determining recessions falls to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), an independent organization supported by grants from government agencies, private foundations, and companies. It’s governed by a Board of Directors consisting of 51 members from leading North American research universities, economics professional organizations, and the business and labor communities. It’s apolitical; it conducts research but does not make policy recommendations or carry out advocacy on the basis of research findings. It has a nearly infinite number of programs, projects, working groups, etc. etc. and publishes more papers than you can shake a stick at.

The NBER is best known among the general public (if at all) for its Business Cycle Dating Committee. This is a committee of eight economists that decides in retrospect the peaks and troughs of the US economy. It defines a recession as “the period between a peak of economic activity and its subsequent trough, or lowest point.” That is, when the economy is not expanding, it’s considered to be in recession.

How do they define a recession? “The NBER’s definition emphasizes that a recession involves a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months. In our interpretation of this definition, we treat the three criteria—depth, diffusion, and duration—as somewhat interchangeable.”’

What criteria do they use specifically?

“Because a recession must influence the economy broadly and not be confined to one sector, the committee emphasizes economy-wide measures of economic activity…These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions.”

In other words, they don’t use any formal definition of a recession – just “we’ll know it when we see it.”

Let’s look at the measures that they specify and see how they’re faring.

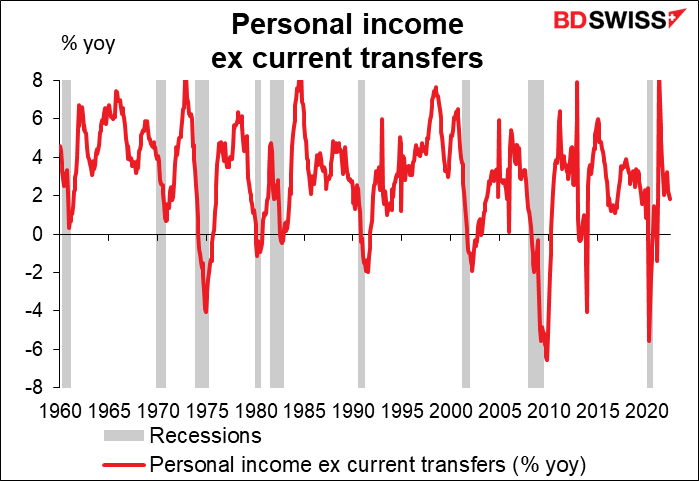

Personal income excluding current transfers: up 1.8% year-on-year. No sign of a recession here.

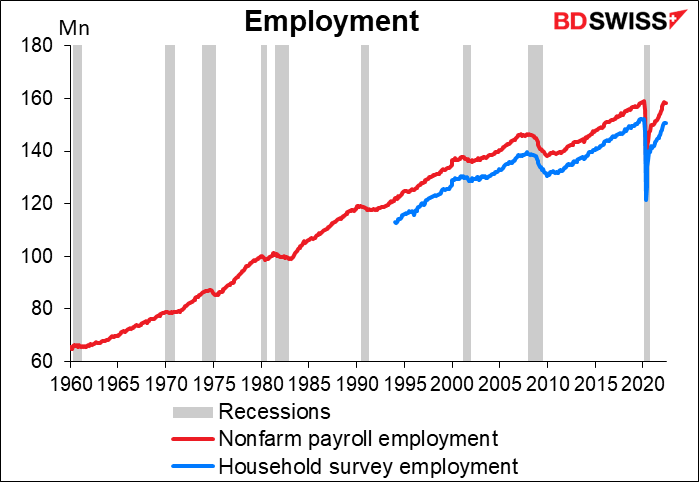

Employment: still going up. Nope, no recession here either.

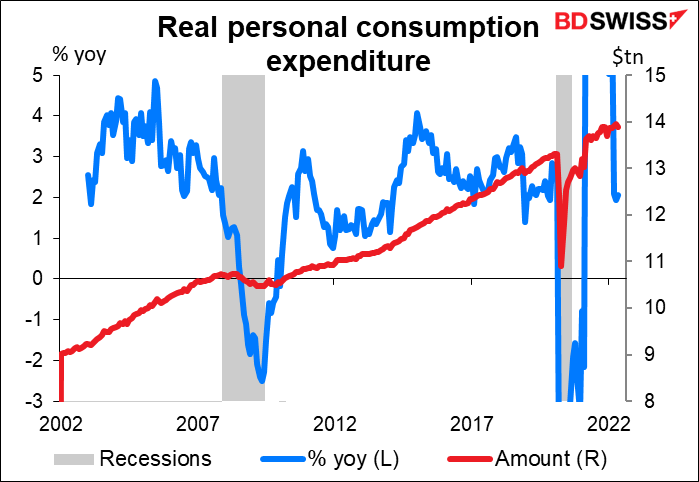

Real personal consumption expenditure: growing by 2.1% yoy. The May figure (the latest) was a bit lower than April, which was peak ($13.895bn vs $13.95bn) but this doesn’t look like a recession either.

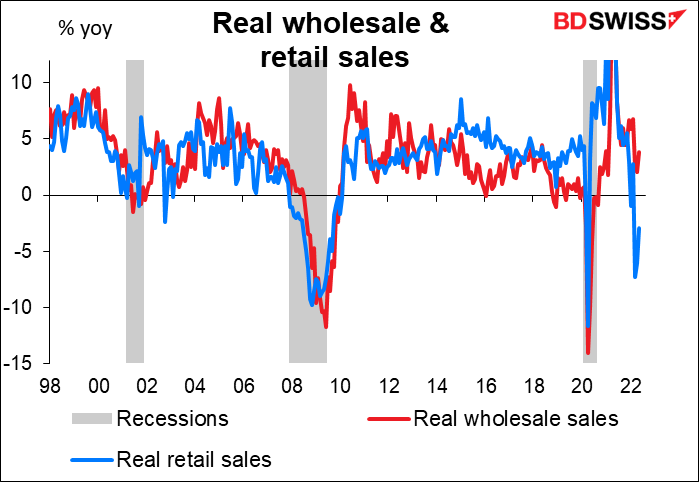

Real wholesale and retail sales: Now we’re getting somewhere! Real retail sales have indeed turned negative. The first hint of a recession! Although real wholesale sales are still up 3.8% yoy.

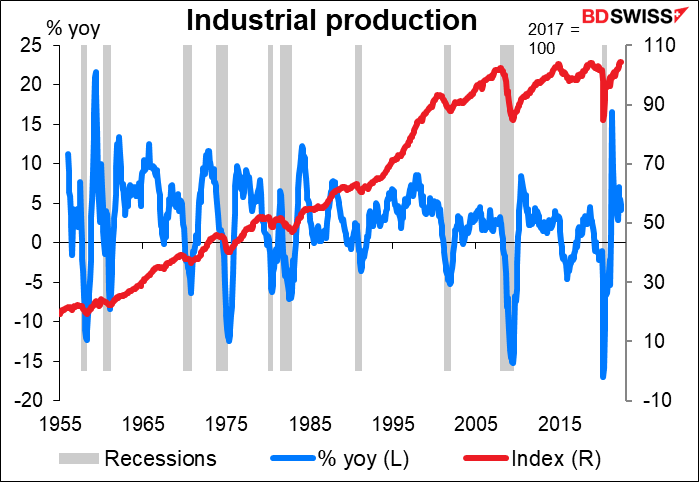

Industrial production: up 4.2% yoy in the latest month. Nothing to see here either.

In short, while US GDP may have fallen for two consecutive quarters, there’s almost no sign that the US is even approaching a recession much less in one. The NBER’s committee said that “In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.” Those two measures are certainly not showing any signs of a recession.

While some people – notably Republicans aiming to besmirch the Biden administration – will try to paint the US as in recession due to two consecutive quarters of contracting GDP, it’s highly improbable that this period will indeed be formally labelled a recession. That’s not to say we won’t have one in the future, and sometime soon even, just that it’s not happening now.

Next week: RBA, Bank of England, and lots of employment data

The parade of rate hikes continues in the coming week with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Tuesday and the Bank of England on Thursday.

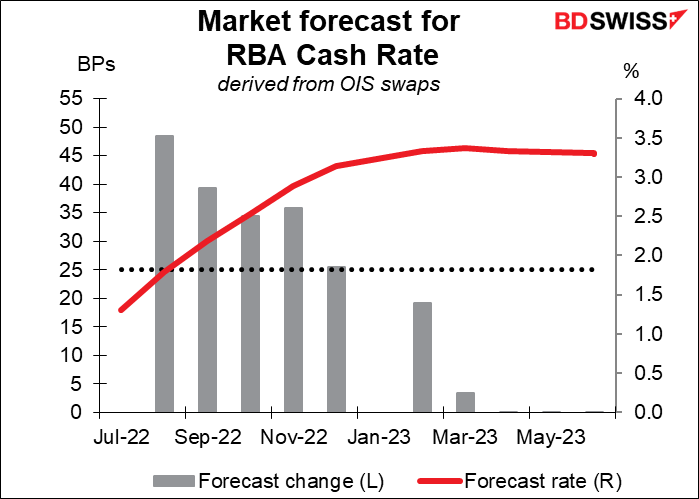

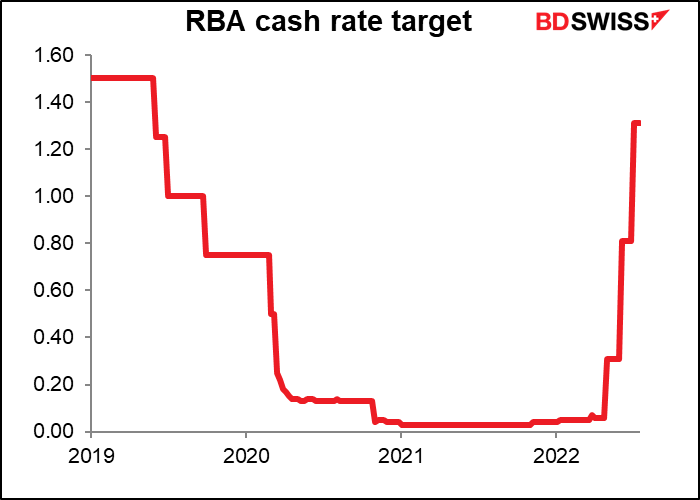

The market forecast for the RBA is +50 bps. That seems about par for the course nowadays.

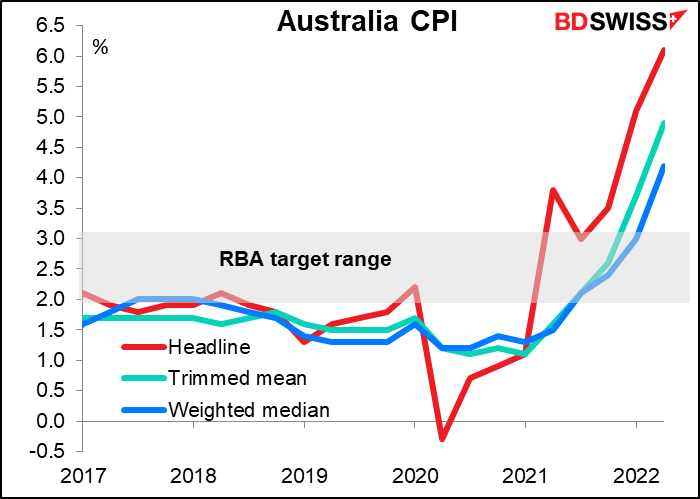

As you may remember, we just got Australia’s Q2 consumer price index (CPI) on Wednesday. It wasn’t as bad as expected but it was plenty bad: headline inflation rose from 5.1% yoy to 6.1% yoy. The quarter-on-quarter rate of +1.8% qoq is pretty near the RBA’s target for a whole year’s inflation (2%-3%). And the two core inflation measures are soaring far far above target, too. Need I say more?

With no sign of inflation slowing, the RBA is going to have to take some strong measures. They hiked by 25 bps in May, 50 bps in June, 50 bps in July…another 50 would seem to be in order at least. The forward guidance is likely to continue to say that the Board “expects to take further steps in the process of normalising monetary conditions in Australia over the months ahead,” i.e. watch out for further rate hikes.

The markets will also be looking forward to the RBA’s revised forecasts on Friday with the release of the August Statement on Monetary Policy.

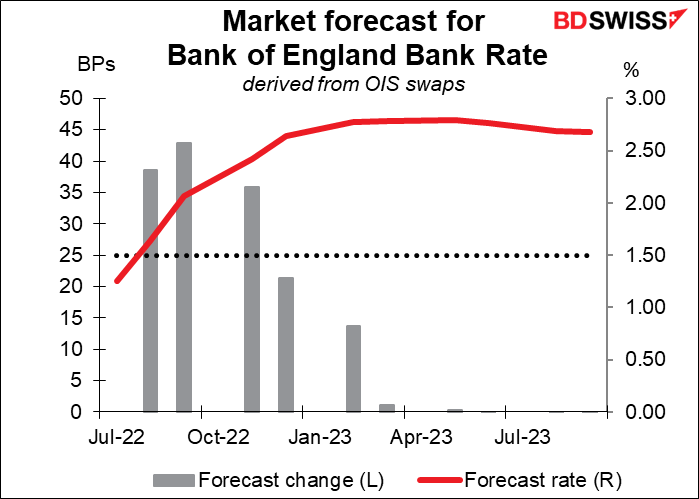

The markets aren’t so sure about the Bank of England. They’ve priced in about a 40 bps hike – i.e. probably 50 bps but not for sure.

One problem is that this will be the last Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting for uber-hawk Michael Saunders, who will ride off into the sunset and be replaced by the more dovish (we believe) Swati Dhingra. So those people who want to see a 50 bps hike are going to make a big push. So far the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street has been one of the more conservative central banks; she hiked 15 bps last December, then 25 bps in February, March, May, and June.

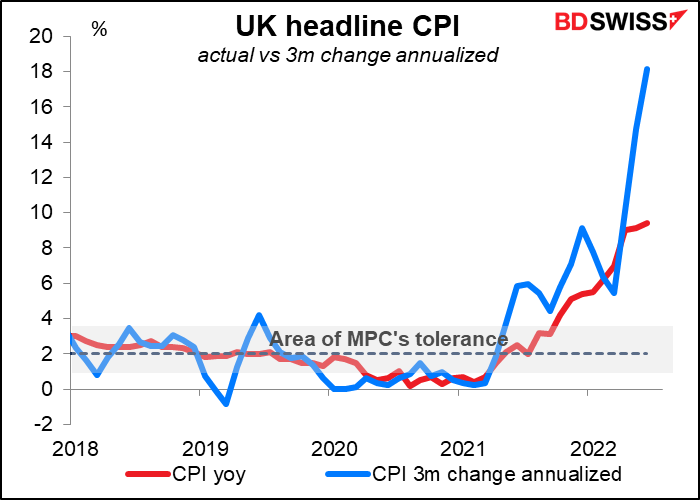

But as I said back in June in my Weekly Outlook, 50 is the new 25. Given that almost all the other central banks are hiking by 50 bps, and a weak sterling pushes up prices, I think they’re likely to go for 50 bps this time. At their last meeting, in June, the MPC said it “will be particularly alert to indications of more persistent inflationary pressures, and will if necessary act forcefully in response.” If headline inflation at 9.4% yoy, up from 9.0% when they last met, doesn’t meet that criterion, then maybe the 3-month change annualized rate of 18.1% yoy will. Failure to hike by 50 bps would be negative for sterling, in my view.

Elsewhere, the theme this week will be on labor market indicators, with the pièce de resistance being of course Friday’s US nonfarm payrolls (NFP).

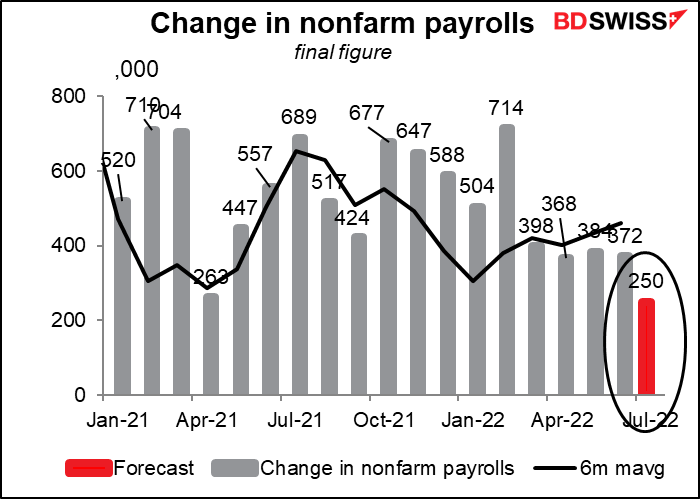

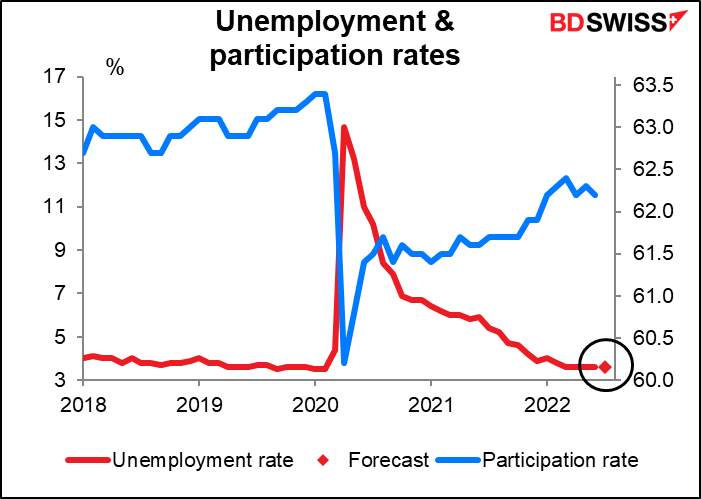

Continuing with the French, the NFP forecasts give me a sense of déjà vu – they’re the same forecasts as last month: NFP of +250k, unemployment rate of 3.6% (which would be the fifth consecutive month at that rate).

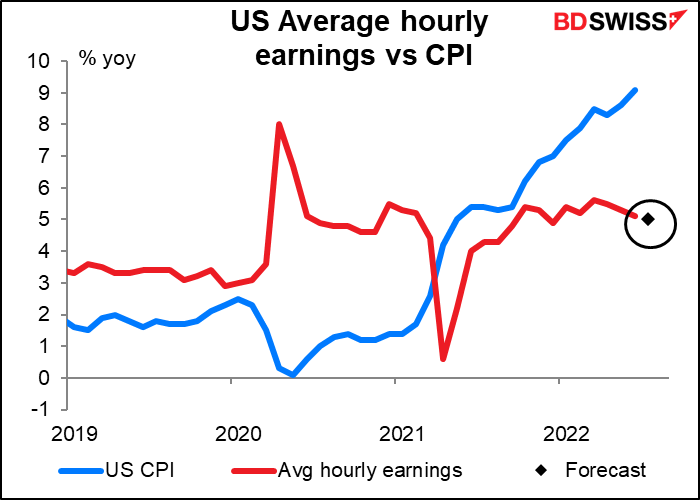

Average hourly earnings are expected to tick down 10 bps to 5.0%. This is far below the inflation rate of 9.1%, meaning workers are still getting the shaft, but it’s higher than the Fed’s preferred inflation rate of 2%, meaning enough to push up inflation in the future.

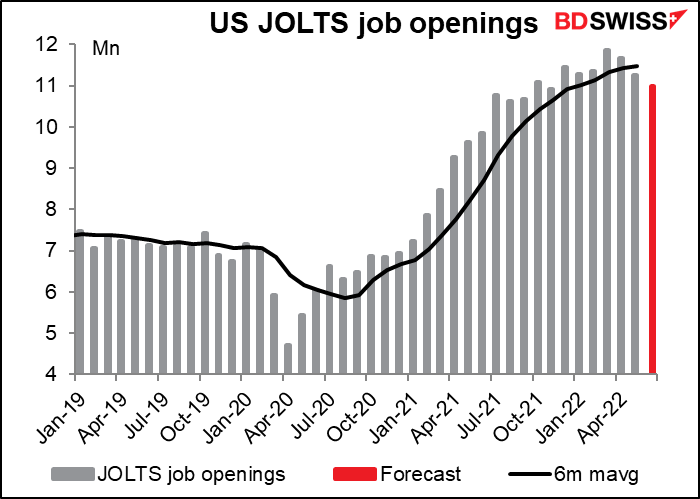

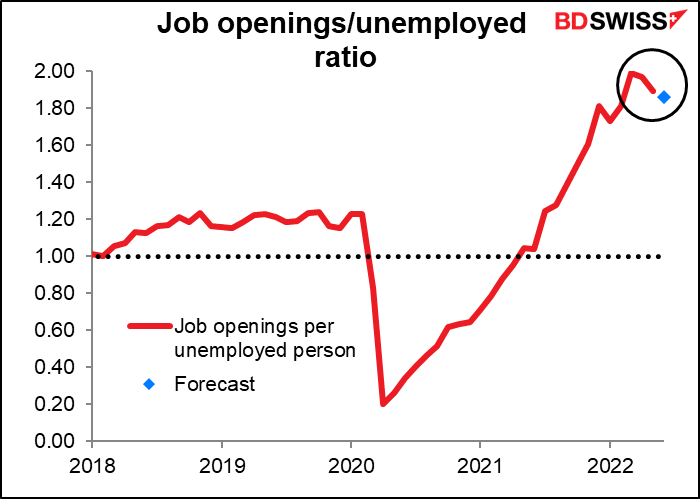

We also get the Job Offers and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) on Tuesday. It’s expected to show only a modest 260k decline in job openings.

At that rate there would still be some 1.86 job openings for every unemployed person.

What did Fed Chair Powell say about employment at his press conference Wednesday?

“… the labor market has remained extremely tight, with the unemployment rate near a 50-year low, job vacancies near historical highs, and wage growth elevated…Labor demand is very strong, while labor supply remains subdued with the labor force participation rate little changed since January. Overall, the continued strength of the labor market suggests that underlying aggregate demand remains solid.”

These figures will do nothing to persuade anyone that the situation has changed. Even if the NFP does come down from the six-month average of 461k, a 250k increase in workers would be substantial. The data as forecast should convince the Fed that “underlying aggregate demand remains solid” and they can keep hiking rates = USD+.

Nonetheless, the impact on the FX market may be muted because of course everyone knows this already. This would be no surprise. For surprises, we should look most carefully at the average hourly earnings (AHE). I think AHE is the most important part of the data, because it’s inflation that worries the Fed most, not the labor market, and pay has the most direct impact on inflation.

Other countries releasing their employment data this coming week include:

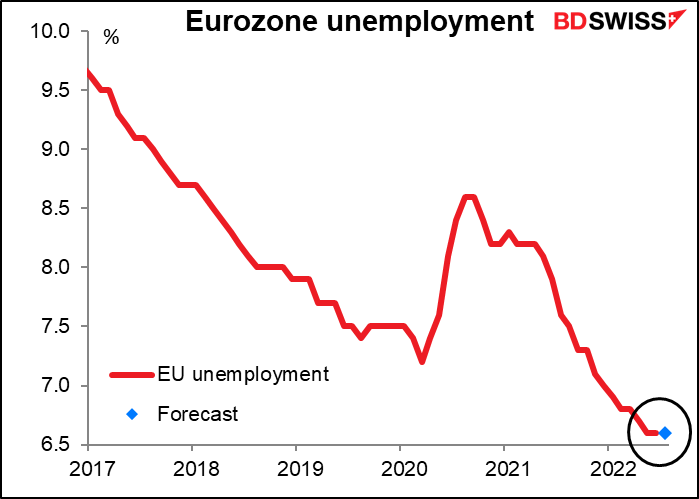

EU (Monday); This isn’t particularly important for the EU, because the European Central Bank (ECB) doesn’t have a “dual mandate” that requires them to watch employment too. They’re required to focus only on inflation. Just FYI though, Eurozone unemployment is forecast to remain at last month’s record-low 6.6% (data back to 1998).

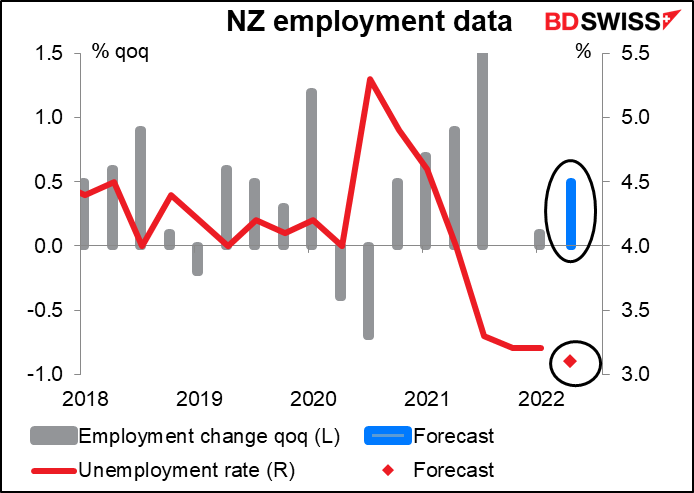

New Zealand (Wednesday): New Zealand does have a dual mandate, but employment isn’t a constraint on the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) at the moment because employment is already well above pre-pandemic levels and the unemployment rate is at a record-low 3.2 (data back to 1985). Unemployment is expected to fall further this quarter too and the number of employed persons to rise further. This will keep the RBNZ free to hike rates further, which should be positive for NZD.

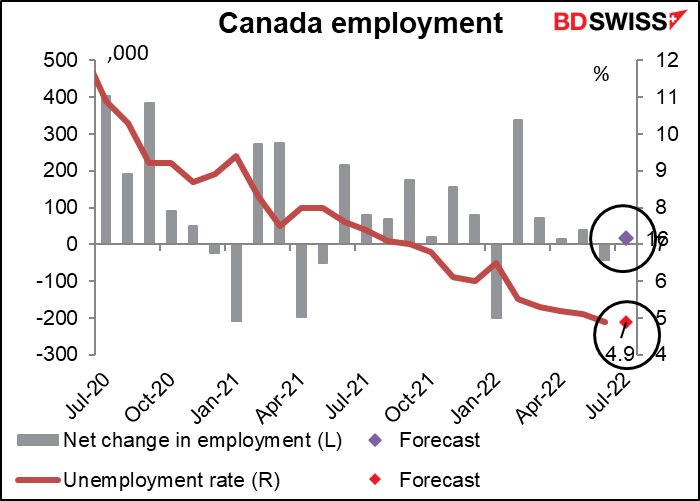

Canada: As usual, Canada will release its employment data at the same time Friday that the US does. The unemployment rate in Canada is expected to remain at the record-low level of 4.9% (data back to 1976) while the number of employed persons is forecast to rise by only a slight 16k, about half the six-month average of 37k. Perhaps Canada too is running out of people who want to work but can’t find job?

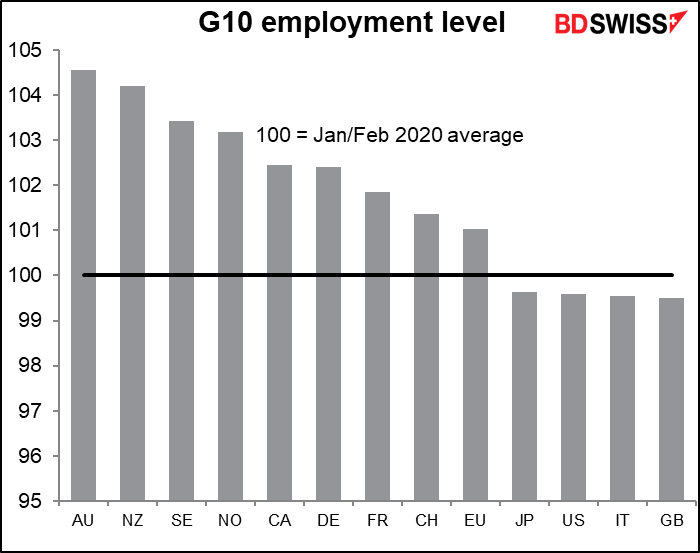

All in all, this coming week’s employment data is expected to show that the employment picture is healthy in most countries. Looking at the G10 countries (including several of the Eurozone countries), only four have yet to return to the pre-pandemic level of employment: Japan, the US, Italy, and the UK.

Other important indicators and events coming up during the week include:

The purchasing managers’ indices (PMIs) for July, the final ones for those countries that have preliminary ones and the one-and-onlies for the others: manufacturing on Monday, service-sector on Wednesday. (Australia, Switzerland, and Canada will be delayed because of holidays in their countries Monday). Along with those comes of course the closely watched US Institute of Supply Management (ISM) versions for the US.

OPEC+ meets on Wednesday. They’ve returned their output to the pre-pandemic level and their quota agreement expires next month, so they may have more room to maneuver — in theory. In fact though most producers are already pumping as much oil as they can. Only a few, Saudi Arabia mostly, have any room to increase production even if they want to. Meanwhile, US President Biden very much does want them to increase production and indeed asked the Saudis for that when he visited the Kingdom in mid-July. How the Saudis respond to the US request will be the focus of this meeting.

Other indicators due out this week include:

- US: factory orders (Wed) and the trade balance (Thu)

- EU: PPI and retail sales (Wed)

- UK: Nationwide house prices (Tue)

- AU: Building approvals (Tue), trade balance (Thu)